National Human Trafficking Prevention Month

January is Human Trafficking Awareness and Prevention Month, a presidentially designated observance designed to educate the public about human trafficking and the role they can play in preventing and responding to human trafficking.

We recently sat down with Dr. Kimberly Chang, family physician and Director of Trafficking and Healthcare Policy at our member community health center, Asian Health Services in Oakland, California. Dr. Chang is also on the President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.

Name: Kimberly Chang, MD, MPH

Name: Kimberly Chang, MD, MPH

Title: Family Physician and Director of Trafficking and Healthcare Policy, Asian Health Services

Guiding quote: Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has. – Margaret Mead

Alameda Health Consortium: Tell us a little bit about yourself

Kimberly Chang, MD, MPH: I am a family doctor and I have been working at Asian Health Services (AHS) for the past 20 years – straight out of residency from University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). I was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii, to a multigenerational Chinese American family, with maybe some Vietnamese and some Hawaiian – it’s difficult to track all the ancestors, but there were some notable ones including a paternal great-grandmother born in Annam (what is now in the northern areas of Vietnam) and was kidnapped off the river while playing one day and sold into child slavery back in the late 1800s. It really struck home that our family history is not so remote and not so different from the issue that so closely relates to the work that I do today.

I attended Columbia University in New York City and majored in liberal arts, and East Asian languages and cultures. I attended Medical School at the University of Hawaii and completed the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard Medical School and earned an MPH at Harvard School of Public Health.

I am also on faculty with Health Partners on IPV + Exploitation, Futures Without Violence, a National Training and Technical Assistance Partner (NTTAP) for the health center program nationwide and am a commissioner appointed to serve on the President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.

AHC: With such an impressive academic and professional background, there were many paths open to you. What led you to working with vulnerable communities at Asian Health Services?

KC: I tried out several types of practice after residency before settling at AHS. I strongly feel that community health centers (CHCs) provide care for patients within the context of their lives and this feels right to me. CHCs look at more than medical histories by really delving into the lives of their patients, where and how they live, work, and play. CHCs excel at looking at how non-medical issues play a role in the overall health of their patients and that often includes looking at the ways in which interpersonal relationships, social involvements, and immigration history impact patient lives.

Additionally, CHCs engage in and are civically active in creating a connected and empowered community. That’s what I love about Asian Health Services and Community Health Centers in general. Our love for the community and the patients is real.

AHC: How did this lead to your work with victims of exploitation and human trafficking?

CLICK to continue reading more about Dr. Chang’s groundbreaking work with victims of exploitation and trafficking

KC: My work in exploitation and human trafficking is grounded in the types of patients we see at AHS. When you look at what makes people vulnerable to labor or sex exploitation or trafficking, it aligns with the social and political drivers of healthcare. The policies and priorities of our society put people in precarity and that precarity creates health vulnerabilities in an already vulnerable and underserved community. Essentially, the patients we see in CHCs are the same people who are disproportionately vulnerable to being exploited and trafficked.

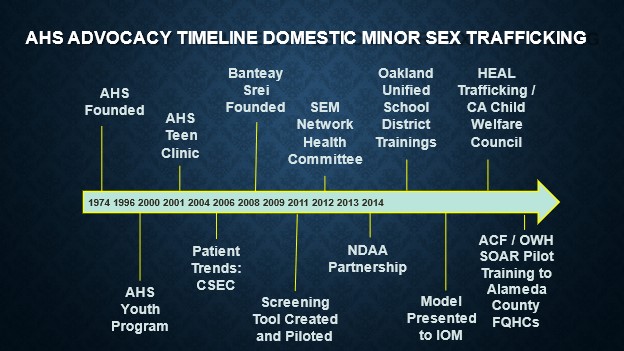

In 2003 I staffed a teen clinic at AHS and had many patients coming in for repeated Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) checks, pregnancy tests, and different episodes of intimate partner violence, and substance use.

At that time, we didn’t really have the language to understand what was going on other than using what are now obsolete terms for prostitution and solicitation. The federal Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA) was passed in 2000 and it defined human trafficking as a crime, but the federal policy definitions had not yet been implemented in California and commercially sexually exploited youth (under 18) were still being arrested and prosecuted for prostitution and solicitation.

In the healthcare field, advocates and survivors began organizing to ensure that the criminal justice system understood and recognized the effects of trauma, the psychological developmental stages of youth, and the need to not further stigmatize and harm these young victims through carceral approaches. I began working in partnership with the National District Attorneys Association to provide a community health and medical perspective through training and technical assistance to the criminal justice sector. AHS helped start a youth development, asset-building organization, Banteay Srei, to help provide prevention and intervention services for these young Southeast Asian women. We also created education modules and clinical protocols so our clinicians could recognize signs of exploitation, how to have conversations with patients, and how to intervene and provide support services. We held convenings and medical and public health conferences at the state, regional, and federal levels. We utilized media platforms to further our outreach, basically I talked with as many people as I could, especially those in positions of influence, to raise as much awareness as I could, and I haven’t stopped.

AHC: Can you break down a little about what this work with victims of trafficking consists of?

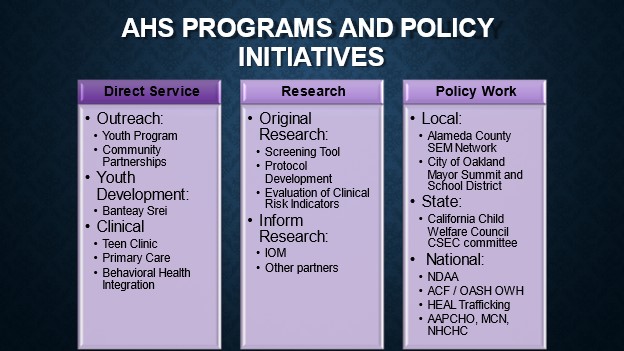

KC: Our work is broken down into phases. As you can see by this chart, we first focus on direct service, then research, and then we begin our policy and advocacy work.

advocacy work.

My work at the federal level began after I completed the Commonwealth Fund Minority Health Policy Fellowship at Harvard University.

After my fellowship I was appointed to the National Advisory Committee on the Sex Trafficking of Children and Youth in the US, formed to provide recommendations to states and the federal government on how to address this issue. I was also invited to give testimony to the Congressional Commission at the US Helsinki Commission, now known as the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe about best practices. Of course I used this opportunity to talk more about the vital role community health centers play in early detection, treatment, and best practices.

In my current role, I see patients and provide direct care. I’m part of the faculty and a thought partner with Health Partners on IPV + Exploitation and assist with trainings and technical assistance, and I work on policy with the President’s Commission on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, as well as serve on the executive board of the National Association of Community Health Centers.

assist with trainings and technical assistance, and I work on policy with the President’s Commission on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, as well as serve on the executive board of the National Association of Community Health Centers.

I’ve continued to write on the issue, stressing the importance of CHCs, community partnerships, and addressing the broader social and political drivers of precarity and vulnerability. You can find links under the Resources section below.

AHC: In what ways are community health centers uniquely positioned to work directly with victims of trafficking?

KC: The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically increased the vulnerabilities that put people at risk of trafficking, as evidenced by a rise in adult cases of human trafficking while abuse among younger cases have been pushed underground. Prevention of violence and continued injury is possible because research has proven that victims of trafficking will seek support from medical practitioners more quickly than from law enforcement if they are treated within a trauma-informed framework. Once medical professionals are trained and knowledgeable about how to leverage community-based support, they interface with survivors in ways in that minimized re-traumatization.

All Alameda County health centers have organized around this work and issue because we know our patients and communities and how they are affected. We convened to develop consistent internal policies and protocols and linkages with community-based organizations supporting victims of trafficking and exploitation. The Alameda Health Consortium sponsored and supported our regional health center work, led by Carla Dartis, formerly of the HEAT (Human Exploitation and Trafficking Institute from Former DA Nancy O’Malley).

AHC: How have you utilized partnerships with other community based organizations to help expand outreach and education?

KC: I work with Health Partners on IPV + Exploitation, Futures Without Violence, which is a NTTAP with Health Resources and Services Administration/Bureau of Primary Health Care to support existing and potential health center grantees and look-alikes on the issues of intimate partner violence and exploitation. They have a broad range of tools to help health centers develop partnerships, implement protocols and policies to serve patients better, and clinical tools to help providers. One benefit of the Health Partners on IPV+E is that they have access to an extensive body of work amongst other projects and programs of Futures Without Violence, like Project Catalyst which helped develop statewide partnerships between Primary Care Associations, state Departments of Public Health, and state Domestic Violence Coalitions to address IPV and Human Trafficking – many health centers nationwide were a part of this project. Helpful tools for health centers can be found here: https://ipvhealthpartners.org/

AHC: There is still a lot to be learned about what human trafficking is. What are some of the misconceptions you wish to dispel right now?

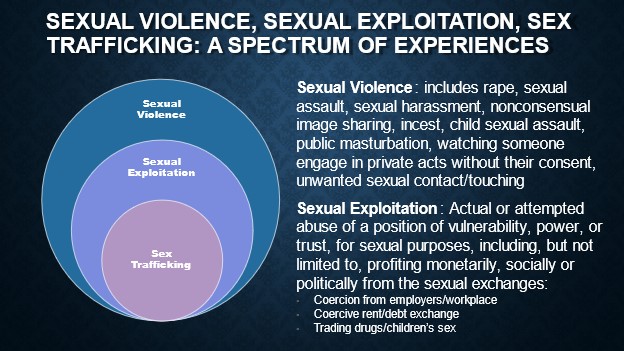

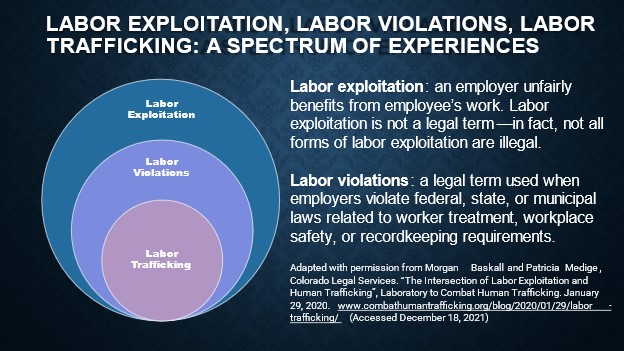

KC: While there is a criminal legal framework and definition of “Human Trafficking” for both sex trafficking and labor trafficking, I really don’t want clinicians, providers, and health centers getting too caught up in those definitions. We aren’t criminal justice investigators or law enforcement professionals – we are healthcare providers.

clinicians, providers, and health centers getting too caught up in those definitions. We aren’t criminal justice investigators or law enforcement professionals – we are healthcare providers.

Victims have many reasons for not engaging with or seeking  assistance from law enforcement and it’s up to us as healthcare providers to provide the best care we can for the person in front of us and help them on their journey to recovery in whatever form that looks like.

assistance from law enforcement and it’s up to us as healthcare providers to provide the best care we can for the person in front of us and help them on their journey to recovery in whatever form that looks like.

AHC: What more can be done to raise awareness?

KC: As CHCs, we of course focus more on a healthcare approach to exploitation as well as focusing on prevention awareness. This means being more civically engaged and bringing more attention to the social factors and policies that make people vulnerable to being exploited. How do we reform policies that make people’s lives precarious? How do we begin to create even wider access to healthcare for all, reforming labor rights, tenants’ rights, immigration, and criminal justice policies? We need to find more ways to bring more vulnerable people into the fold of care and protection by expanding access to services across the board.

AHC: What are the signs of someone being trafficked and how can the average person assist?

KC: Signs of exploitation and trafficking overlap with those of intimate partner violence, and other types of violence. Vulnerable people don’t have power or control over their situations. There are of course visible signs of abuse, but there are also hidden signs and situations that we need to parse out to determine exploitation. Factors like substance use disorders, housing instability, lack of control over legal documents, reproductive coercion, and sexual violence are all part of being exploited and often trafficked.

Health Centers can focus on 1) implementing privacy, safety, and confidentiality policies to protect patients; 2) implement protocols with linkages to support services that include: legal services, behavioral health services, substance use treatment, housing, domestic violence, and trafficking advocates; 3) train providers on how to provide education, screening, treatment, and follow-up.

There are great tools and a template clinical protocol available here: https://healthpartnersipve.org/general-resources/. This template protocol was informed by Alameda Health Consortium’s Human Trafficking-Medical Offramps Project.

AHC: The fact that there is a month devoted to bringing about awareness and educating the public about human trafficking indicates that there is more global action being taken to address and eliminate trafficking. What are your thoughts on this?

KC: I think it’s great to have a month dedicated to raising awareness about exploitation and human trafficking, but there are more traditional, on the ground ways in which we can raise additional awareness and support victims. We need to bring more attention to the root causes of trafficking and exploitation and that includes exposing and eliminating the systems and structures that incentivize profiting off human exploitation. We also need to expand access to and grow current systems that provide care and protection to those who are survivors. We have a long road ahead of us, but I also know the power of community health centers and what we can accomplish when we’re equipped with the right tools and support.

Resources:

Links to articles written by Dr. Chang

- Medical-Legal Collaboration and Community Partnerships: Prioritizing Prevention of Human Trafficking in Federally Qualified Health Centers in 2020

- Child trafficking and exploitation: Historical roots, preventive policies, and the Pediatrician’s role in 2022,

- The Historical Roots of Human Trafficking: Informing Primary Prevention of Commercialized Violence in 2021.

You can find more resources HERE.

You can learn more about Asian Health Services HERE.